The Cambodian Campaign of 1970 and the Role of Mike Mansfield in

Expanding the Influence of the Senate in Foreign Policy

By Nolan Franti, August 2012

On April 30, 1970, President Richard Nixon announced a limited U.S. invasion of Cambodia as the next phase in the ongoing war against communist North Vietnam. This action followed the overthrow of Cambodia’s neutralist government under Prince Sihanouk in March, and its replacement by a pro-Western regime under General Lon Nol. Nixon labeled the Cambodian campaign an “incursion.” He claimed that the limited invasion was necessary to clear out the North Vietnamese Army’s communist “sanctuaries” in the Fish Hook region of eastern Cambodia and bring about “peace with honor” in South Vietnam.[1]

A storm of anti-war protest across the United States following Nixon’s announcement marked turning point in domestic opposition to the war.[2] The public’s negative reaction to the Cambodian campaign played a crucial role in convincing Congress to adopt a more active stance in ending America’s military involvement in Vietnam. As Senate Majority Leader, Mike Mansfield was one of several Senators most closely identified with the fight to end the war through legislation. Initially a strong believer in the primacy of the Executive branch in foreign policy, Mansfield came to question and eventually sought to limit the president’s power to wage war without the consent of Congress.[3] The opposition of Mansfield’s constituents to the expansion of the war into Cambodia in large part precipitated his own decision to oppose the war more actively through legislation.

In the wake of the commencement of the Cambodian campaign, American citizens from across the country wrote to their elected representatives to register their support for or opposition to President Nixon’s decision. The mail the Senate alone received was so voluminous that “mailbags were stacked in Senate corridors for want of a place to process them in senators’ offices.”[4] As Senate Majority Leader, Mansfield received a large volume of mail regarding the Cambodian invasion. The vast majority of these letters—according to some estimates by as much as 20 to 1—opposed the President’s expansion of the war into Cambodia.[5]

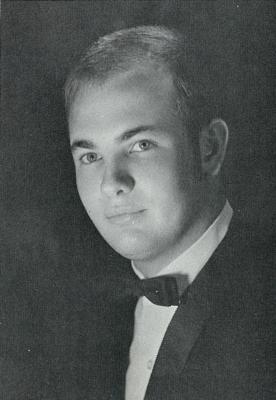

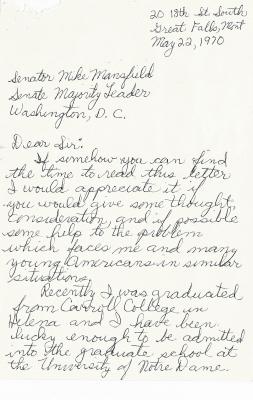

A young graduate student and Montanan named Michael Lopach wrote one such letter to Mansfield on May 22, 1970. Lopach expressed his dismay at learning that his student draft deferment was set to expire and that he might soon face deployment in Vietnam, a conflict he had come to consider “not at all . . . just” and “not a direct threat to my country.”[6] Lopach stressed that he was not opposed to war as a matter of principle. Rather, his determination that U.S. involvement in Vietnam was unjust had led him to decide “that in the event I am faced with orders to go to Vietnam I will refuse to obey them.”[7] In his letter to Senator Mansfield, Lopach asked the senator “to help me in any way you can, whether through a letter to my draft board, through legislation to end the war, or any other means at your disposal.”[8] Showing his support for the aims of the campus protests across America, if not for their methods, Lopach ended with the hope for “the United States to be a better place, free from the necessity for riots & National Guard takeovers”[9]—a reference to the May 4 incident at Kent State in which National Guardsmen had shot and killed four students during an anti-war demonstration.[10]

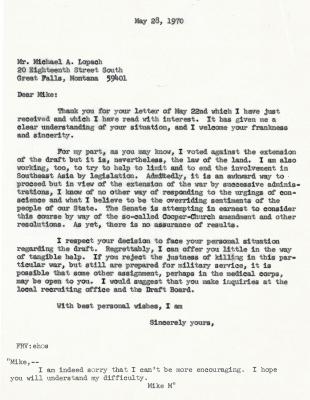

Mansfield’s detailed response to Lopach’s letter showed the depth of his sincerity for his constituents’ concerns as well as his newfound determination to end the war through legislation. Though expressing his regret that “I can offer you little in the way of tangible help,” Mansfield wrote, “I respect your decision to face your personal situation regarding the draft.” Regarding Lopach’s request to act “through legislation to end the war,” Mansfield replied “I am also working…to try to limit and end the involvement in Southeast Asia by legislation.” Although Mansfield noted that “admittedly, it [legislation] is an awkward way to proceed” in ending U.S. involvement, he added, “I know of no other way of responding to the urges of conscience and what I believe to be the overriding sentiments of the people of our state.”[11] Adding a personal note from one Mike to another, Mansfield’s written postscript to the letter, copied in ink over the carbon copy, reads, “Mike—I am indeed sorry that I can’t be more encouraging. I hope you will understand my difficulty. Mike M.”[12] The addendum was a touching reflection of Mansfield’s sympathy for Lopach’s position and his own frustration at his inability to end a war that he believed had needlessly consumed the lives of over 50,000 of America’s finest young men.[13]

Mansfield put his words into action by supporting the Cooper-Church Amendment, sponsored by Senators John Sherman Cooper (R-Kentucky) and Frank Church (D-Idaho), which sought to enforce President Nixon’s promise to withdraw U.S. troops from Cambodia by June 30, 1970 and to limit U.S. bombing of Cambodia thereafter.[14] The Senate passed the amendment on June 30, but it was defeated in the House. A modified version of the bill ultimately passed both houses of Congress and was signed by President Nixon on December 22, 1970. The compromise bill prohibited the introduction of ground troops into Laos and Thailand, but not Cambodia, where U.S. combat operations had ended earlier that year.[15] The McGovern-Hatfield amendment, sponsored by Senators George McGovern (D-S.D.) and Mark Hatfield (R-Or.), would have ended all involvement in Vietnam by July of 1971. The bill never reached the President’s desk, as it was defeated in the Senate in spite of Mansfield’s support.[16]

The efforts of Mansfield to end the war via legislation did eventually bear fruit, however. The Senate first passed a series of non-binding resolutions known as the Mansfield Amendments, which urged an end to the war in Vietnam.[17] After these Amendments failed to gain traction, in October 1971 the Senate, at Mansfield’s urging, refused to pass the Foreign Authorization Act after the removal of a clause in the bill that would have limited military involvement in Vietnam. This was the first time the Senate had rejected the Act since its creation following World War II. Then, in January of 1972, Congress passed and Nixon signed a bill that included a provision ordering the “prompt” removal of U.S. forces from Indochina, subject to the release of American POWs, although Nixon vowed to ignore the provision to withdraw troops.[18]

Perhaps the most significant attempt to limit the President’s power to wage war indiscriminately came the following year, in 1973, when Congress passed the War Powers Act over Nixon’s veto. The Act required the President to inform Congress within two days of committing American troops in action in any foreign country and to end their deployment after 90 days unless Congress authorized further military action.[19] Though almost every U.S. President has challenged either the Act’s constitutionality or its reach since its passage,[20] it remains an expression of Congress’s desire to constrain the executive branch’s war powers.

Mansfield’s commitment to ending the country’s military involvement in a war he felt was “unnecessary, unwarranted, and uncalled for” never wavered during his congressional career.[21] Initially, that commitment had taken the form of a passive opposition by counseling an end to the war while continuing to fund the war in Congress.[22] By leading the Congressional effort to de-fund military operations in Cambodia and Vietnam and to pass the War Powers resolution, however, Mansfield changed the nature of his opposition and helped change the debate over how the power to wage war would be shared between the executive and legislative branches.

Questions about the essay can be sent to library.archives@umontana.edu.